Detectarea altor universuri

If there are other universes out there—as some scientists propose—then one or more of them might be detectable, a new study suggests.

Such a finding, “while currently speculative even in principle, and probably far-off in practice, would surely constitute an epochal discovery,” researchers wrote in a paper detailing their study. The work appears in the September issue of the research journal Physical Review D.

Cosmologists generally hold that even if other universes exist, a controversial idea itself, they wouldn’t be visible, and that testing for their existence would be hard at best.

But the new study, by three scientists at the

“The question of what the aftermath of a collision might be is still quite open,” wrote Matthew C. Johnson, one of the researchers, in an email. One theory even holds that a clash between universes could destroy the cosmos we know. But Johnson, now at the California Institute of Technology in

Several lines of reasoning in modern physics have led to proposals that there are other universes. It’s a rather dodgy concept on its face, because strictly speaking, “the universe” means everything that exists. But in practice, cosmologists often loosen the definition and just speak of “a universe” as some sort of self-enclosed whole with its own physical laws.

Such a picture, in concept, allows for other universes with different laws. These realms are often called “bubble universes” or “pocket universes”—partly to sidestep the awkward definitional issue, and partly because many theorists do indeed portray them as bubble-like.

A key thread of reasoning behind the idea of bubble universes, which are sometimes collectively called a “multiverse,” is the finding that seemingly empty space contains energy, known as vacuum energy. Some theorize that under certain circumstances this energy can be converted into an explosively growing, new universe—the same process believed to have given rise to ours. Theoretical physicists including Michio Kaku of city College of New York argue that this might go on constantly—he has called it a “continual genesis”—creating many universes, coexisting not unlike bubbles in a foamy bath.

How might one detect another universe? Johnson and his colleagues reason that any collision between bubbles would, like all collisions, produce aftereffects that propagate into both chambers. These effects would probably take the form of some material ejected into both sides, Johnson said, although just what is unknown. This would in turn affect the distribution of matter in each pocket universe.

If such collisions happened recently, they might be undetectable because our universe might be too huge to be markedly affected; but not so if the events took place long enough ago, according to the University of California team, whose paper is also posted online. If a knock occurred when our expanding universe was still very small, they argue, then the aftermath might still be visible, blown up in size along with everything else since then.

When the universe was less than a thousandth its present size, it’s thought to have undergone a transformation. As it expanded, it became cool enough for atoms to form. It then also became transparent. Before that, everything had been a thick fog, but with tiny variations in its density at different points; denser parts would eventually grow and coalesce into galaxies.

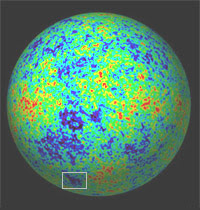

This fog is still visible, because many of the light waves it gave off are just now reaching us: this is how astronomers explain a faint glow that permeates space, called the cosmic microwave background. It represents the edge of our visible universe and is detected in all directions of the sky.

A collision would lead to a rearranged pattern of density fluctuations in this background, according to the

“Nothing like this has presently been observed, although no one has ever looked for this particular signal,” Johnson added.

On the other hand, researchers have found at least one striking irregularity in the background glow—a “cold spot,” thought to be related to a vast and anomalous void in the cosmos. Could that be the mark of a separate universe? “I’m going to remain completely noncommittal” on that, Johnson said. “I can’t even tell you if it would be a hot spot or a cold spot.” Temperature variations in the cosmic microwave background are believed to reflect density variations in the early universe.

Johnson and colleagues stressed that their proposal may be only the beginning of a long, painstaking research program. “Connecting this prediction to real observational signatures will entail both difficult and comprehensive future work (and probably no small measure of good luck),” they wrote. But “it appears worth pursuing.”

Comments